If you're serious about getting better at chess, learning to read notation is non-negotiable. It’s the language of the game, and fluency is your ticket to studying historic matches, following along with grandmaster commentary, and—most importantly—finding the critical mistakes in your own games.

Think of it this way: you can't truly appreciate classic literature if you can't read. Playing chess without knowing notation is the same kind of handicap. You're effectively cut off from centuries of chess wisdom and the brilliant insights being shared by top players today.

The Key to Unlocking Chess Knowledge

Learning notation isn't just about ticking a box. It’s the tool that bridges the gap between being a casual player and becoming a serious student of the game. Once you grasp it, a whole world of resources suddenly becomes available.

All those legendary games you've heard about? They're no longer just stories. You can actually play through them yourself. Mastering notation gives you access to:

- Classic Game Anthologies: Books filled with the brilliant games of Fischer, Kasparov, and Carlsen finally make sense. You can see their genius unfold on the board, move by move.

- Live Tournament Broadcasts: You can follow expert analysis during major events, understanding precisely what the commentators are discussing.

- Powerful Analysis Tools: Chess databases and engines, which rely on notation, can help you analyze millions of games to find patterns and improve your own strategic thinking.

The single greatest benefit, in my experience, is the ability to review your own games. Going over your scoresheet lets you pinpoint the exact moment a game slipped away, spot your recurring bad habits, and build a much stronger, more informed strategy for next time.

A Language with a Rich History

While it might feel like a modern system, algebraic notation has surprisingly deep roots. Early versions of it appeared in a French manuscript way back in 1173. Of course, it took a while to catch on. It wasn't until 1981 that FIDE, the international chess federation, officially made it the global standard, finally replacing older, more descriptive (and often confusing) methods.

There's a good reason it won out. The logic and clarity of algebraic notation are what have allowed it to endure for so long. If you're curious, you can dig into the full story by exploring the history of algebraic notation) and see why it became the undisputed language of the game.

Mastering the Chessboard and Its Coordinates

Before you can record a single move, you have to know the battlefield. The chessboard is a perfect 8x8 grid of 64 alternating squares, but it’s more than that. To truly understand chess notation, you must see the board as a map, complete with a precise coordinate system.

Think of it like GPS for your army. Every single square has a unique address, which is the foundation of the algebraic notation system. This universal language ensures that a move like "Nf3" means the exact same thing to a player in Moscow as it does to one in Minnesota, providing an unambiguous location for every action in the game.

Decoding Files and Ranks

The board’s grid is defined by two simple concepts: files and ranks. Getting these down is the first real step toward fluency.

- Files are the eight vertical columns that run up and down the board. From White’s perspective, they are labeled with lowercase letters, from 'a' through 'h', starting on the left.

- Ranks are the eight horizontal rows that go across the board. These are numbered '1' to '8', starting from White’s side.

A square's name is simply the combination of its file letter and rank number. For instance, the intersection of the 'e' file and the '4th' rank gives us the square e4, a very famous starting point for countless games.

A crucial point I always stress to new players is that the board's orientation is fixed. The a1 square is always the dark-colored corner on White's left, no matter which color you're playing. This consistent perspective is what makes the notation so reliable.

Of course, these coordinates only make sense if the board is set up correctly. If you're ever in doubt, our guide on how to set up a chess board correctly will get you on the right track from the very first move.

Practical Exercises to Build Fluency

Reading about coordinates is one thing, but internalizing them is what truly matters. Your goal should be to glance at the board and instantly identify any square without having to count from the edge. Repetition is your best friend here.

Try these simple drills I've used for years to sharpen this skill:

- Random Square Drill: Close your eyes, drop a pawn or your finger onto a random square, then open your eyes and name its coordinates as fast as you can. "g5," "c2," "h8."

- Color Association: Take the first drill a step further. When you name the square, also identify its color. For example, say "f3 is a dark square" or "d4 is a light square." This builds a much richer mental map of the board.

- Diagonal Tracing: Place a bishop on a corner, like f1. As you slide it along its longest path, call out every square it touches: "e2, d3, c4, b5, a6." This is fantastic for seeing the board dynamically.

Just five minutes of these drills before you play can make a massive difference. With consistent practice, navigating the board will become second nature, setting you up perfectly for tracking piece movements.

Recording Basic Piece and Pawn Moves

Once you have a feel for the board's coordinates, we can get into the heart of the matter: recording the action. At its core, the language of chess notation is quite elegant. It simply combines a piece's identity with its destination square. This is the foundation for reading and writing any chess game, whether it's a quiet opening or a chaotic tactical scramble.

First things first, you need to know the shorthand for your pieces. Each one gets a single, capitalized letter, making algebraic notation a truly universal standard.

- K for King

- Q for Queen

- R for Rook

- B for Bishop

- N for Knight

You've probably noticed the Knight uses an N. This is a critical detail to prevent any mix-ups with the King. Just think 'N' for kNight, and you'll get it right every time.

The Basic Move Formula

To write down a move, you just put the piece's initial next to its destination square. It's that simple. For example, if you slide your Bishop to the c4 square, you'd jot down Bc4. A Rook landing on d8? That's Rd8. It’s a clean, two-part instruction: which piece moved, and where did it go?

Let's look at a common opening move. Say you're playing White and want to bring your kingside knight into the action, moving it from g1 to f3. You simply write Nf3.

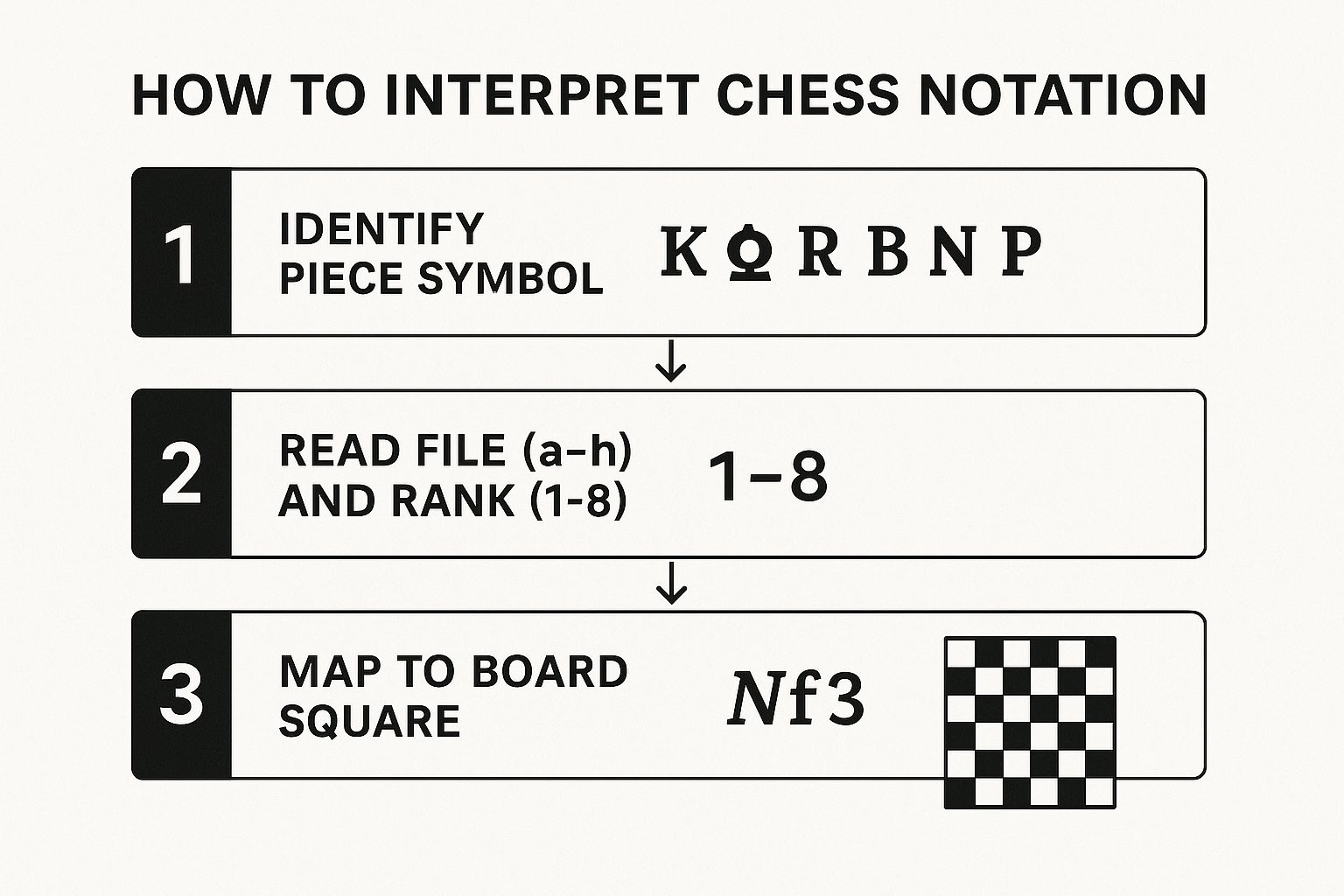

This visual guide neatly summarizes how to interpret a standard move.

As you can see, it breaks down into a simple thought process: identify the piece, find the coordinate, and execute the move. This becomes second nature with a little practice.

The Exception for Pawns

Pawns are the humble foot soldiers of the board, and they have their own special rule in notation. They're the only pieces that do not get an initial. Since pawn moves are by far the most common, leaving out the 'P' keeps the game record clean and much easier to scan.

So, if you see a move written with only a destination square, like e4, you know instantly it's a pawn move. This is the most popular opening move in history, and you'll never see it written as "Pe4." Just the destination is all you need.

This distinction is absolutely vital. The move d4 means a pawn has moved to that square. In sharp contrast, Nd4 means a Knight has landed on the very same square. The presence or absence of that single capital letter tells you everything.

To really get the hang of this, nothing beats practicing on a quality board where the coordinates are clearly marked. For anyone just starting their journey, our guide to the 7 best chess sets for beginners can point you toward a set that makes the learning process a pleasure. Having a good, functional board in front of you makes translating notation into real moves far more intuitive.

How to Notate Captures and Checks

Knowing how to record a simple move is a great start, but the real story of a chess game is told through its conflicts. To truly follow along, you need to understand how we document the most critical moments on the board. Captures, checks, and the game-ending checkmate each have their own symbol, adding a layer of drama to any scoresheet.

The system itself is beautifully simple. When one piece takes another, we just place an ‘x’ between the piece's symbol and its destination square. This little character signifies that an opposing piece has been removed from the board—a pivotal event in any match.

For example, if a White Bishop on c3 were to capture a Black Knight sitting on e5, we would write that move as Bxe5. The 'x' makes it instantly clear that a capture happened on the e5 square.

The Special Case of Pawn Captures

Pawn moves have their own quirks, and captures are no different. Since pawns don't get a capital letter initial, we need a slightly different approach to keep things clear. When a pawn captures, we identify it by its starting file.

Let's say a White pawn on the e-file captures something on the d5 square. The correct notation is exd5. This tells you everything you need to know: the pawn from the 'e' file captured on 'd5'. This method is essential for avoiding confusion when two different pawns could have made the same capture.

This kind of precision is exactly why algebraic notation became the universal standard. Its logical framework is surprisingly quick to pick up. The rise of personal computers in the 1980s was a huge catalyst for its adoption, with some reports from that time suggesting a beginner could learn the basics in just 15 minutes. You can get a feel for this historic transition by reading archived discussions from early computer magazines.

Indicating Threats to the King

Beyond captures, notation also has to track direct threats against the most important piece of all: the king. These moves often represent major turning points that can swing the momentum of a game.

We use two primary symbols for these royal threats:

- Check (+): When a move puts the opponent's king under direct attack, we add a plus sign to the end of the move. Moving a Queen to h5 to attack the king would be written as Qh5+.

- Checkmate (#): When a move puts the king in check with no legal way to escape, ending the game, we use a hash symbol. That final, winning blow might look something like Qf7#.

Now, let's bring these concepts together and see how they look in a real sequence. The following moves are from a well-known, aggressive opening:

- e4 e5 (Standard opening, both sides advance their King's pawn.)

- Nf3 Nc6 (Both players develop their knights.)

- Bc4 Nf6 (Bishops enter the game, eyeing key diagonals.)

- Ng5 d5 (White puts pressure on a weak pawn; Black challenges in the center.)

- exd5 Nxd5 (White's pawn captures, and Black's knight immediately recaptures.)

- Nxf7 Kxf7 (White sacrifices the knight to expose the Black king, who is forced to capture.)

- Qf3+ (White’s queen jumps in, delivering another check.)

Following this short exchange, you can see how the 'x' and '+' symbols create a clear, dynamic narrative of the action on the board. Mastering these notations is a must for anyone who wants to study chess games seriously and improve their own play.

Documenting Special Moves and Ambiguous Situations

Basic moves and captures are the bread and butter of chess notation, but the game has a few quirky rules that demand their own special symbols. Getting these down is what separates someone who can sort-of follow a game from someone who can read a scoresheet with total confidence. Once you know these, you're ready for pretty much anything.

Let's start with castling, the only move that involves two of your own pieces at once. It’s a vital defensive maneuver that tucks your king away and brings a rook into the game. Thankfully, its notation is refreshingly simple and doesn't use coordinates at all.

- Kingside Castling (Short): This is recorded simply as O-O.

- Queenside Castling (Long): The slightly longer version is noted as O-O-O.

Next up is pawn promotion. When one of your pawns makes the long journey to the other side of the board (the 8th rank for White, the 1st for Black), it gets a powerful upgrade. It must become a queen, rook, bishop, or knight. To write this, you record the pawn's move and then add an equals sign followed by the initial of the new piece. For example, if a pawn on b7 pushes to b8 and becomes a queen, you'd write b8=Q.

Handling Ambiguous Moves

The whole point of algebraic notation is clarity. But what happens when two identical pieces can move to the very same square? This is called an ambiguous move, and we have a simple system to clear up any confusion.

Imagine you have two rooks on your back rank, one on a1 and another on f1. Both of them can legally slide over to d1. Just writing Rd1 wouldn't work—which rook moved? To solve this, we add just enough information to make it clear. We specify the file the piece came from.

- The rook from the a-file moves: Rad1.

- The rook from the f-file moves: Rfd1.

This little addition tells the whole story. The same logic applies if the pieces are on the same file. Say you have knights on g1 and g5, and either could jump to f3. You’d use the rank to distinguish them: N1f3 or N5f3.

A key principle here is to be economical. Only add the file or the rank if you absolutely have to. If specifying the file resolves the ambiguity, there’s no need to also add the rank. Keeping the notation clean is just as important as keeping it clear.

Notating The En Passant Capture

The last piece of the puzzle is the en passant capture, a French term meaning "in passing." This is a special power for pawns. It's only possible on the turn immediately after your opponent moves a pawn two squares forward to land right next to one of your pawns.

Recording an en passant capture is handled just like a regular pawn capture. You write the file of the pawn doing the capturing, an 'x' for the capture, and the square it lands on. So, if your pawn on e5 captures a Black pawn that just landed on d5, the notation is exd6. Notice the destination square is d6—the square your pawn moves to, not the square the opposing pawn was on.

With castling, promotion, disambiguation, and en passant under your belt, you’ve essentially mastered the language of chess. You now have the skills to follow along with master-level games and, just as importantly, to accurately record your own.

Common Questions About Reading Chess Notation

As you get more comfortable with the basics, you'll naturally run into some finer points that can be a bit confusing. These are the questions almost every player asks when they're learning the language of the game. Let's clear up some of the most common ones.

Working through these details is what really solidifies your understanding, turning a jumble of letters and numbers into a clear story of the game.

Algebraic Versus Descriptive Notation

One of the first potential trip-ups is the difference between algebraic notation—the system we use today—and its older predecessor, descriptive notation. This guide is all about the algebraic system, where every square has a single, fixed name, like e4 or g8, no matter whose turn it is.

Descriptive notation, which you might see in older chess books, was a bit more complicated. It named squares from each player's point of view. A square might be called "King's Bishop 3" for White, but that same square would be "King's Bishop 6" for Black. It was this potential for confusion that led FIDE, the international chess federation, to officially adopt the much clearer algebraic system as the global standard back in 1981.

The real power of algebraic notation lies in its universal simplicity. A move like Nf3 means the exact same thing to a player in Moscow, Mumbai, or Minneapolis. This common language is the foundation for the massive online databases and powerful analysis engines that are central to modern chess.

The Mystery of the Missing Pawn Initial

"Why don't pawn moves start with a 'P'?" This is a classic question. We use a letter for every other piece, so it seems odd that pawn moves like e4 are just... a square name. The answer is all about efficiency.

Think about it: pawns are by far the most numerous pieces, and in any given game, they make more moves than anything else. By simply omitting the 'P', the notation becomes significantly cleaner and easier to read at a glance. It's a clever shorthand. Since every other piece is identified, any move notation without a piece initial is automatically understood to be a pawn move. Simple.

The only time you'll see a pawn specified is during a capture, like exd5. Here, the 'e' clarifies that it was the pawn on the e-file that made the capture, keeping the record perfectly accurate without cluttering up every single pawn push.

Putting Your Knowledge into Practice

So, how do you go from reading about notation to actually using it? The key is to jump right in and get your hands dirty. Don't just stare at the theory; make it physical.

A fantastic way to start is by playing through famous games. Look up some "miniatures"—short, sharp games that are usually under 25 moves. They're packed with action and are quick to get through.

Here’s a simple, hands-on approach:

- First, set up a real or digital chessboard in front of you.

- Next, find a game with notation. A classic match from a world champion is always a great choice.

- Read the first pair of moves, for example: 1. e4 e5.

- Then, physically make those moves on your board.

- Keep going, one move at a time, until you've played through the whole game.

This process builds a powerful link between the symbols on the page and the movement of the pieces. You'll quickly find yourself internalizing the patterns, and soon you'll start to see the moves on the scoresheet come to life in your mind. To take your game to the next level, check out our guide on 8 essential chess tactics for beginners in 2025, which will help you recognize winning opportunities as you analyze these games.

At MarbleCultures, we believe that a beautiful game deserves to be played on a beautiful board. You can elevate your own chess experience with one of our handcrafted marble and metallic chess sets. They're designed for the dedicated player but also serve as a stunning work of art for your home. Discover the perfect blend of strategy and style at MarbleCultures.